2014-23 Insects of Surinam series: photographs of collages, high-reliefs and animation

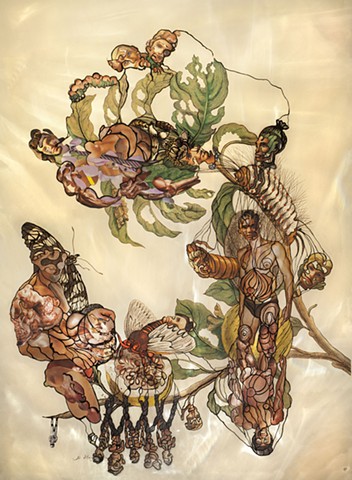

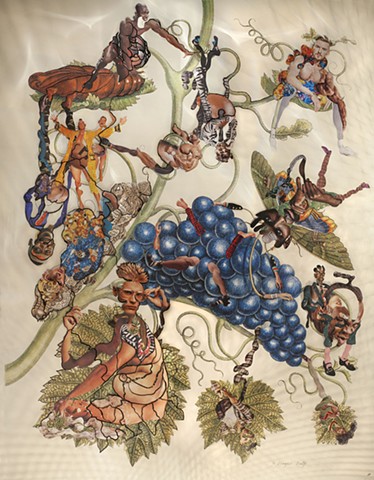

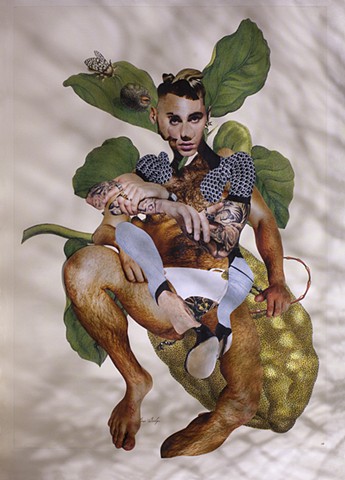

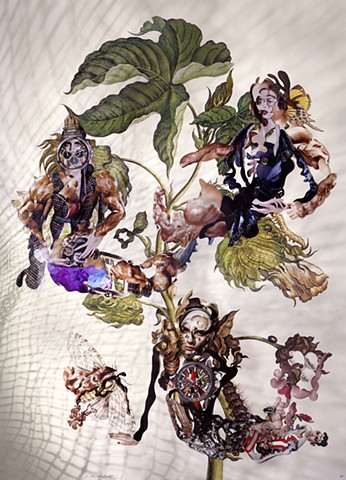

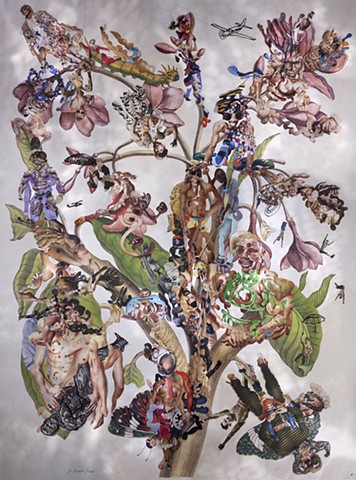

Dominique Paul plays with the representation of the body and explores its transformation. This notion of body transformation informs Paul’s fantastical invention of hybrid creatures. In her Insects of Suriname series, the lacy cutouts of bodybuilder’s flesh from magazines are buoyed by colorful consumer products. The surrealistic scenes share space with flora and insects illustrated by Maria S. Merian, a Baroque-era naturalist documenting metamorphosis of insects. Taking the form of a botanical mandala, Paul strives to express a sense of urgency in the playing fields of our human-centric society that overuses the planet’s resources. Paul boldly envisions a future where the genetic code of living organisms is altered, and a strange new hierarchy among sentient beings emerges.

Text about this series located after the images of this portfolio: Playing Fields: Reconnecting with an Idea of Nature

Please click on the image below to start the animation

Playing Fields: Reconnecting with an Idea of Nature

I am writing from a British colony, subject to the Queen, from the closest Canadian city to New York where I exhibit and have my second practice, which consists in performing in the public space with interactive wearables addressing social and environmental issues. Canada “started” as a French colony, where my ancestors emigrated in the 17th century. A vast country with natural resources, a land which is still being plundered as we are becoming a hub for the video games industry and artificial intelligence research. However, the land was already populated by First Nations, transmitting it to the next generation, as they received it. We invaded their territory, where they lived in a sustainable way. Today, they are on the frontline to challenge in court the non-sustainable projects still being put forward. Their culture is our hope to guide us and inspire us in developing a respectful relationship with nature.

This is my context as a cultural hybrid, and a woman. Society insists that my ability to reproduce should differentiate me so much from the other gender. Despite this cultural pressure, I do not feel this polarity. I just feel human and I am grateful to the LGBTQ community who are fighting for their rights to be part of the social fabric. In short, we are all humans presenting a rich spectrum of diversity, not a rigid dichotomy (Insects of Surinam 28). However, as much as it is important to embrace diversity, the Western way of life is threatening biodiversity. We are disconnected from the cycle of life, the effects that our choices have on ecosystems. We are out of touch and generally we have no idea of the impact of our daily consumption, of the food we eat and the objects we buy. How are they produced, are they sustainable or toxic?

In 2010, I came across a new publication presenting in an exquisite way Maria Sybilla Merian’s complete Insects of Surinam series of botanical illustrations of plants and their inhabiting insects. Some of these plants were later being cultivated on a large scale and still subject to intensive agriculture today: the Anthropocene could have been named the Plantationocene. Sadly, the plantations in the Americas were concurrent with slavery. Today there is a term to inspire a better relationship: “Planthroposcene, which is an aspirational episteme or scene in which we seed solidarities with the plants”i.

Merian was a Baroque-era naturalist and pioneer in documenting the different forms of the metamorphosis of insects in their habitat, under the guidance of natives. She crossed the Atlantic in the Age of Discovery, as my ancestors had settled in New France. As I opened the book, I was enthralled and envisioned it as a stage to play with the male body represented as an object of desire, as a new territory for marketing products: males and females, we are all objects now! Merian was observing nature as part of a collective effort to better understand and document the world. In the studio, I create encounters between her plants and insects with today’s reshaped and retouched flesh (Insects of Surinam 4, 2011 & 20, 2014). The figures are mainly male to reflect upon who holds power today and females are often augmented such that they are better “equipped” in their attempt to be part of the action (Insects of Surinam 25-26, 2017). I strive to be inclusive, however, the deep tanned flesh is often undistinguishable from the flesh of people of color. Printing a plant two meters high, it becomes a tree invaded by a stylish mob led by a Pied Piper (Insects of Surinam 23-24, 2017). I draw lines to connect the elements composing the hybrid figures, often presenting a gestating abdomen, with the vegetation (Insects of Surinam 31-32). The aesthetic standard for the torso may be interpreted as a form of armor that I associate to the exoskeleton of insects. I am now making an exoskeleton for my images with a laser as I cut the print to the image and insert it between two sheets of recycled plexiglass. With this technique, I have assembled or “grafted” seven plants to form a tree of life (Insects of Surinam 34 and 35, 2019).

The approach is playful, cutting out remodeled bodies, using their muscular flesh, as if cultured in a petri dish, disconnected from the individual, as a mere raw material, when genetic engineering is using a very precise tool, CRISPR “scissors”. I am merging body tissues with a stylized representation of nature, where the pattern of the printed magazine image meets the engraved lines. To photograph the collage, the scene is lit through recycled containers as if the plant was under a canopy. I then print it on a thick matte photo rag paper to unify the glossy magazine paper with the colored engraving. I play with the scale, as smaller beings are now inhabiting the plants. My scissors are extracting organic shapes to create hybrid forms, uniting flesh with insects and plants, combining humans, planes and watches, to form cyborg figures. In a new project, I am documenting endangered species of wild bees. I began by drawing the bees and during this process I have developed a relation of empathy towards them. I would like to transfer this emotion to the viewer to reconnect us to what sustains us (Bombus occidentalis mckayi or Western Bumble Bee, 2019).

Today we have embodied technology in our consciousness, we stand so close that we cannot take a distance from it.ii As time is running out, hence the watches, let us be creative at reinventing the relationship we have with nature instead of behaving like an invading species (Insects of Surinam 23 & 24, 2017). As Donna Haraway had envisioned in her Cyborg Manifesto, in the 80s, the transformations at play from the “White Capitalist Patriarchy” to “Informatics of Domination”, from “Mind” to “Artificial Intelligence”, and from “Sex” to “Genetic Engineering”. She used the cyborg as an ironic figure to reinvent nature: “A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world-changing fiction.”iii

i Meredith Evans, “Becoming Sensor in the Planthroposcene: An Interview with Natasha Myers.” Visual and New Media Review, Fieldsights, July 9 2020. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/becoming-sensor-an-interview-with-natasha-myers

ii Jaak Tomberg, “On the “Double Vision” of Realism and SF Estrangement in William Gibson’s Bigend Trilogy,” in Science Fiction Studies 2013, 40.2, n° 120, pp. 263-285.

iii Donna Haraway,“Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991), pp.149-181.

Bibliography

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Merian, Maria S. and Katharina Schmidt-Loske. Insects of Surinam: Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, 1705. Köln: Taschen, 2009.

Paul, Dominique. Entre chair et lumière: De la possibilité d’une distance critique par l’objet-image. Paris : L’Harmattan, 2019.